The greatest milestone in David Schlueter’s recovery from a motorcycle crash has been his return to the glass studio.

The day before Easter Sunday four years ago, a normal motorcycle ride turned ugly for David Schlueter. He was hit by another driver and severely injured, even more than he realized until his orthopedic surgeon put bleak words to the trauma. “The bone breakage I had was major, and the tissue damage was catastrophic,” David says. “My Achilles tendon and calf on my left leg were completely severed, and my foot was turned in a complete circle. I have had nine surgeries, and I still have more coming up.”

Since his first surgery on Easter Sunday in 2015, David has felt the impact of the crash over and over again, with every step he takes, every moment he lingers over a task, a movement or a thought that wouldn’t have given him pause four years ago. “I still have a wheelchair in the back,” David says, motioning behind him in his shop in Old Town Helena, Buck Creek Stained Glass. “It just took a long time to get to a point where I’m functional. I fight pain on a daily basis.”

David’s mobility was extremely limited for more than a year after the accident, forcing him to put his work at the shop on hold. He struggled to regain use of his left arm, a frustrating setback to this ambidextrous man. “To be restricted to one arm was a pain.”

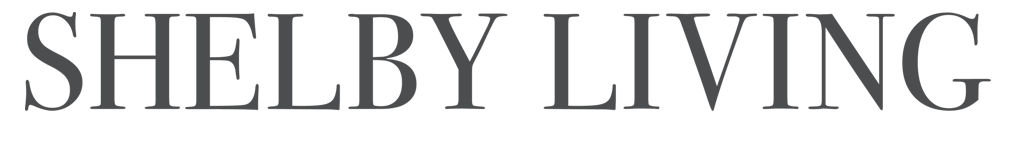

But this former Marine would not be deterred from returning to the shop—and returning to his Harley. “Of course I ride motorcycles again,” he says, no trace of hesitancy in his voice. “I’m a little slower, but this is what I do.”

To look around his shop, you might think David has worked with glass his whole life. (To be fair, he has done it for about 30 years.) But there was a period in his adulthood, before he traded suits and ties for jeans and T-shirts, when he didn’t.

He worked for Pricewaterhouse, one of the world’s largest accounting firms, while living in Florida. Between client meetings and work obligations, he took classes at a local glass studio. Working with glass had intrigued him ever since he watched the activity inside a studio he passed walking home from school when he was younger. “I just thought it was the coolest thing in the world to watch somebody cut glass,” he says. “I’ve just always been fascinated by it.”

When David’s company’s intended merger with another company fell through, he was among hundreds of employees who were laid off. He had been helping out at the glass studio already, where he was asked to join the staff. He worked his way up to lead artist. Meanwhile, he eventually accepted an offer to oversee the finances of a manufacturing company in Helena, and moved his family to Alabama.

But, once again, he felt drawn back to glass. “I was like, ‘Why don’t I open up a studio?’ And he did. Nine years ago, he opened Buck Creek Stained Glass in a storefront in Old Town Helena. His income dropped significantly, but perks of doing what he loves and running his own business have made up for it. “I haven’t had a dry cleaning bill in 10 years,” he says. “I haven’t been on a plane in 10 years. I walk in the door of my studio, and I get to play all day long.”

He sold the first glass panel he made at Helena’s Buck Creek Festival, and started teaching classes to help generate more revenue. Restoration projects account for nearly 90 percent of what he does, though, because in his words, “not many people do what I do.”

Every restoration project is different because every piece requires different amounts of work and time. “Sometimes it’s quick and inexpensive,” he says. “Sometimes it’s a total rebuild. I have had repairs that have taken a couple years.”

David restored one of the original front doors of the chapel in St. Vincent’s hospital in Birmingham. The project took more than two years to complete, but it was a labor of love for him. “That’s probably my favorite restoration.”

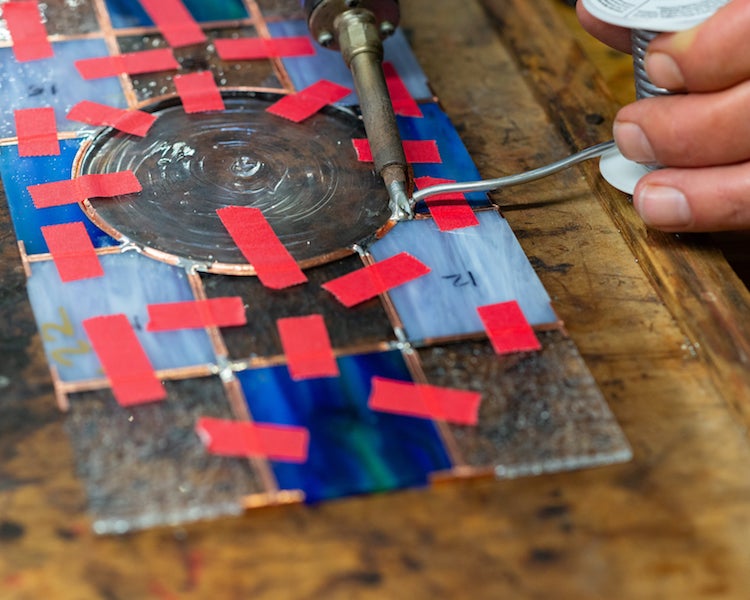

He also restored a shattered church window from Germany that came to him in numerous fragments of different shapes and sizes … like a large glass puzzle with no picture for reference. As painstaking as it was, David completed it. “There’s an art component to stained glass—the design—but the cool part is the technical part of having the skills and putting it all together … and hopefully doing it better than anybody else does.”

The goal of restoration projects is to make the pieces look like “what happened never happened,” David says. That’s why his technical skills with glass come in handy in these projects. “It doesn’t come with blueprints,” he adds. “It gets challenging sometimes, aggravating.”

David Schlueter works on many restoration projects, like this shattered church window from Germany he pieced back together again. (Contributed)

The other side of his business is creation. This is where David’s artistic abilities shine, in everything from windows to doors to decorative pieces bearing the likeness of a family’s beloved pet. “It’s hands-on and one of the few glass arts other than glass blowing that you have instant gratification,” he says. “I like to watch it take shape.”

One of David’s crowning career achievements, as he calls them, is having someone recognize his work by his abstract, swooping-arc style. They might even say, “You’re the glass guy.” He embraces the nickname as much as every day he can spend working at the shop, where a parrot named Biscuit, a cat named Muffin and music from the radio keep him company. “I love what I do,” he says. “I think I have the coolest job on the planet.”