Artists add horse hair to raku poetry for unique designs

Written by Emily Sparacino

Photos by Keith McCoy

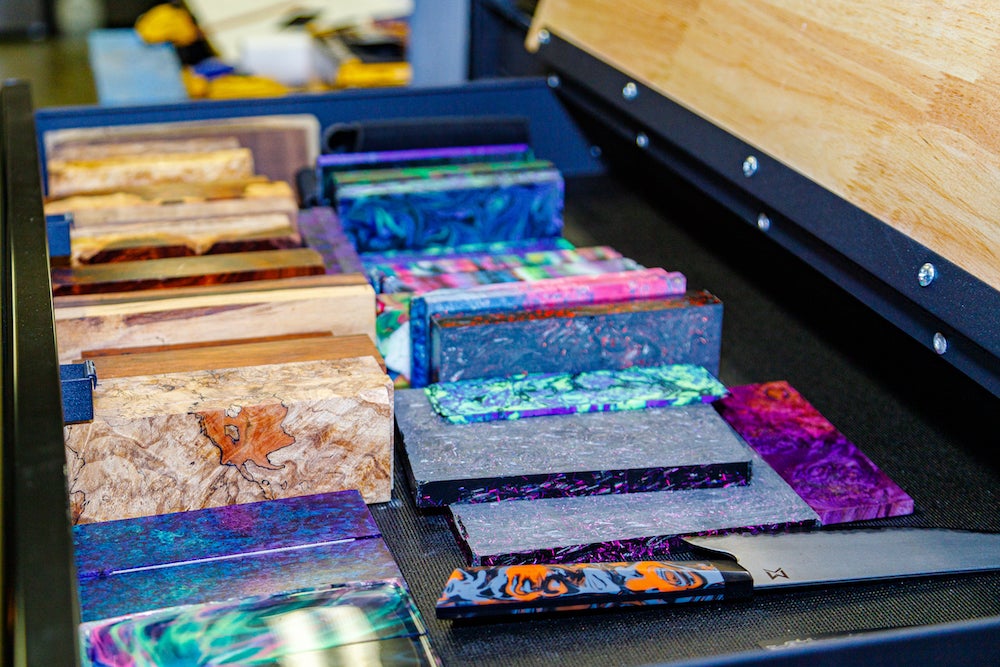

Friends Sandra Annonio and Stephanie Dikis never know exactly what they’ll get when they create pieces of raku pottery for their equine collection.

It all depends on heat, timing and an element of surprise: horse hair.

“It’s like Christmas every time,” Annonio said, as she and Dikis prepared to take heated pieces out of their raku kiln and apply strands of horse hair to them for spectators at Columbiana’s Cowboy Day in February. “You never get tired of it.”

Annonio and Dikis started making raku pottery together in December 2015, after taking a class with sculptor Nelson Grice at the Shelby County Arts Council.

Raku pottery is made using a type of porous clay that can withstand swings in temperature without cracking or splitting, Annonio said.

“Raku pottery will take the thermal shock of the heat,” she added. “It’s more organic, the raku. We like the idea of it being a more freeform, organic shape. We’re in the early stages of perfecting our craft.”

As they delved into raku pottery, the pair started adding strands of hair from horses’ tails to the surface of the pieces, a technique Annonio saw in a demonstration in Asheville, North Carolina.

“It’s got to be horse hair,” Annonio said, noting the thickness of horse hair, compared to human hair, is what allows it to work. “It’s different. It’s unique.”

The multi-step process of making their horse hair raku pottery for their County Road Raku line is one that Dikis and Annonio only do at certain times, depending on the temperature outside.

“It’s not optimal when it’s too hot or too cold,” Annonio said.

Using a raku kiln they constructed from a special kit, Annonio and Dikis fire raku pieces once, take them out and allow them to fully cool, and then put them back in the kiln in the bisque stage––when they are fired but unglazed––to heat them to roughly 1,000 degrees with an open flame from a torch.

As soon as they are thoroughly heated, Annonio and Dikis have only a few minutes to remove them from the kiln and apply strands of horse hair to their surfaces. If they don’t work quickly enough, the pieces become too cool for the hair to adhere.

“It takes two of us to do it,” Annonio said. “The pieces must be so hot for horse hair to bond.”

After the finished pieces have cooled, Annonio and Dikis rinse them off with water to remove the excess carbon residue.

“It’s kind of random. It’s as quick as you can do it,” Dikis said of the process. “We love surprises. We can control amount of hair, but not design.”

They said they receive hair donations for the pottery from local “horse enthusiasts,” and they do custom pieces with hair from customers’ horses upon request.

They can also apply different glazes to their raku pieces.

“Raku is not just for horse hair,” Dikis said. “There are so many variables. I’m sure we’ll continue to learn.”

Most of the raku is handmade, not thrown, Annonio said.

The porous nature of the clay renders it unsafe for food use, but Annonio and Dikis also make and sell traditional, functional pottery.

“We love regular pottery, too,” Annonio said.

They live about four miles away from each other on the same county road, hence the name of their line, County Road Raku.

Annonio and Dikis will be selling their pottery at The Marketplace at Lee Branch on June 3, July 8 and Aug. 19.

To follow their adventures with horse hair raku, visit Facebook.com/countyroadraku/.

“I’m learning every time I do it,” Dikis said. “It’s never-ending.”