By Anna Grace Moore

Photos Contributed

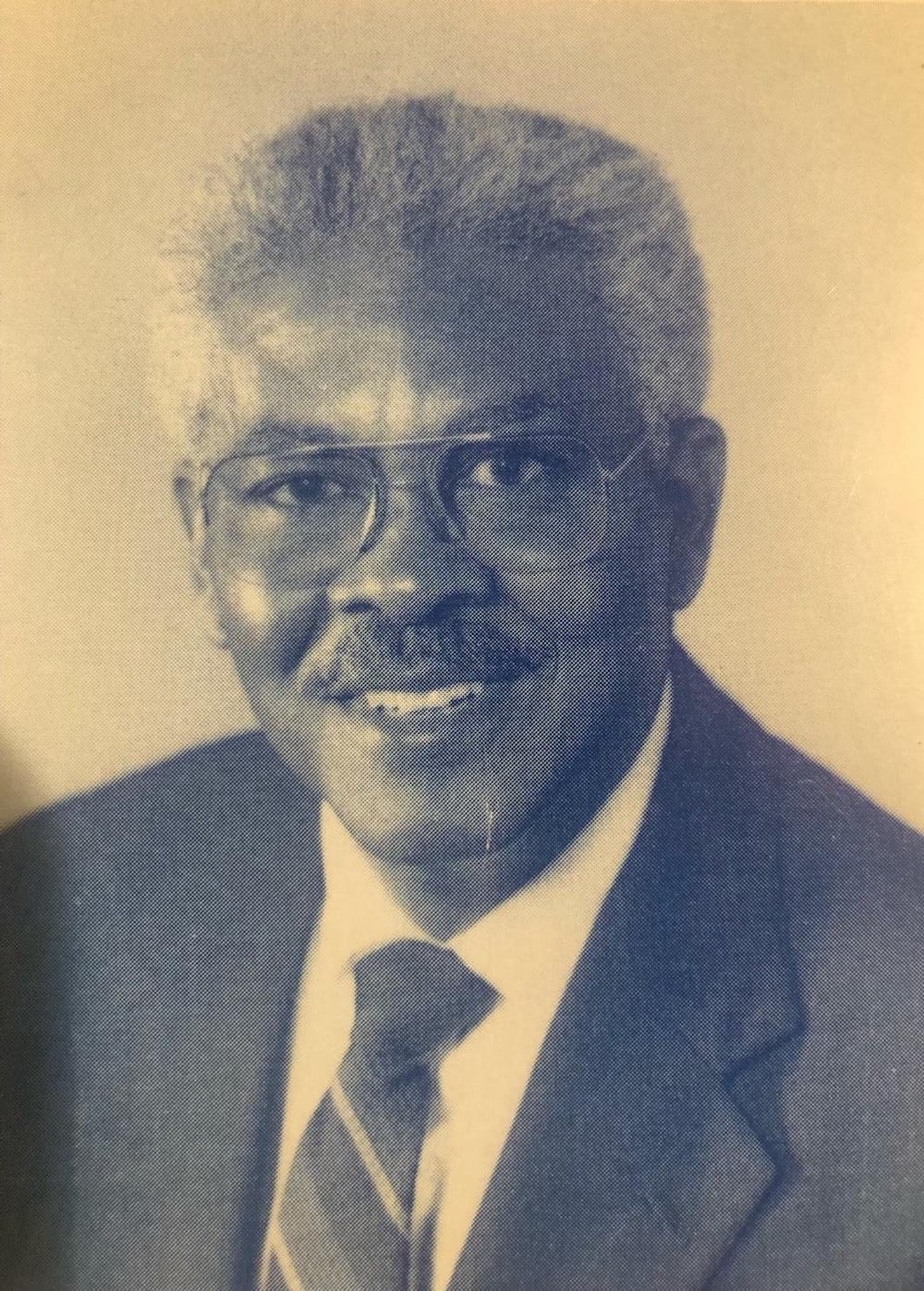

Hailing from Atmore, Alabama, George Dailey was born on March 19, 1928 to Frank and Ophelia Dailey. As he grew, so did his tenacious spirit–his love of learning and his desire to make his mark on the world.

George attended Escambia County Training School and went on to earn his bachelor’s degree in history and mathematics and his master’s degree in education from Alabama State University. In 1953, George began teaching history and coaching boys basketball at the all-black Shelby County Training School.

There, George built relationships with his students, instilling in each of them the confidence to pursue their dreams. Despite the Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court ruling in 1954, most schools were not desegregated until many years later. George, even still, continuously advocated for equal opportunities for his students.

“He was such a role model and a catalyst for social reform,” says Sylvia Vassar, a board member of the Shelby County Historical Society Museum & Archives. “He was an outstanding leader in the community who focused on improving education and the quality of life for everyone regardless of race or gender. He was a strong supporter of the equal rights movement and advocated for diversity, equality and inclusion within Shelby County Schools and the city. There were times when he came up against opposition, but he never did throw in the towel. It was probably very difficult for him, but he never gave up, and he preserved.”

Jewel Dailey, George’s wife, remembers first meeting him at a teacher’s conference in September 1956. George’s charming smile first caught her attention, but his exuberant passion for his students captivated her heart. Jewel taught English and social studies at the Shelby County Training School alongside George, and over the years, the two formed a budding friendship before tying the knot several years later.

Jewel says one of George’s favorite aspects of teaching and coaching were watching his students excel in their endeavors. At the time, Shelby County Training School did not receive a lot of funding, so the basketball team had to play outside in often extreme temperatures. To encourage his players, George would practice with them, ensuring games stayed lighthearted and fun.

In 1965, George became the principal of Prentice High School, which was the city of Montevallo’s only all-black high school that was first founded in 1950. During this time, George fought hard for integration, becoming a pillar of the Civil Rights Movement here in Shelby County.

In 1968–notably 14 years after Brown v. Board of Education–students were given a “freedom of choice” letter, meaning black students would indefinitely have the freedom to choose what school they wished to attend for the 1968-69 school year.

In 1970, the Prentice student body merged with Montevallo High School, and George became one of the assistant principals at the newly integrated school. Prentice High School then became Montevallo Middle School.

“I was told he was very good at calming any conflicts that arose between the white and the black students during this process,” David Nolen, the Shelby County Historical Society Museum & Archives’ board president, says. “He was known as an individual who looked out for the welfare of all of his students.”

George took it upon himself to ensure every student was treated fairly, prompting him to work for the Shelby County Board of Education. George became the Shelby County supervisor of secondary instruction in 1971, and later on, he became the coordinator of secondary education.

In 1984, George became elected to the Montevallo City Council, making him the first-ever African American to hold office in the council. George wanted all constituents’ voices to be heard, so he worked to disband at-large voting, meaning city councilors would be elected by districts. This movement George is credited for starting as he believed the minority vote would be protected.

After serving on the Montevallo City Council, George ran and became elected to the Shelby County Commission District 2 in 1990, once again making him the first person of color to serve on the Commission.

“He wanted to break down the walls of segregation within the schools and within the communities,” Sylvia says. “He was a role model for African Americans.”

Montevallo City Councilman Kenneth Dukes agrees. Kenneth was in his youth when George was elected as county commissioner, and he says watching a black man achieve what had never been accomplished thus far was incredible.

“George would empower you with understanding and knowledge, but most of all, to respect everybody,” Kenneth says. “He was a blessing to me and helped me be the type of person I am now.”

In 1991, George retired from the Shelby County Schools system after an extensive 38-year-long career. During his 14-year-long tenure with the Shelby County Commission, George ensured that his communities’ needs were met.

At the time, the communities in District 2 were less affluent and struggled to get county funding to replace the water and sewage systems in the area. Numerous residents could have suffered from severe health conditions resulting from contaminated water.

While many constituents voices’ went unheard, George listened intently, working to secure funding to restore the water systems. Among the many service projects George oversaw, it would be his efforts politically that would define his career.

At age 75, George was called home to heaven on Sept. 29, 2003. Today, his legacy lives on through George Dailey Park, which was built by the city of Montevallo and is located in front of Montevallo Middle School.

Thanks to George, Shelby County experienced decades of peace during a politically polarizing era following desegregation. Children–both black and white–had a bulldog in their corner, fighting for their rights to a good education. People of color had their voices heard and their votes protected.

Shelby County owes a debt of gratitude to George Dailey. However, knowing his personality, George would just say to “pay it forward with a smile.” May all learn to “live like Dailey.”